Indigenous peoples of Khakassia. Khakas people Traditional activities of Khakass

Khakass (self-name Tadar, Khoorai), obsolete name Minusinsk, Abakan (Yenisei), Achinsk Tatars (Turks) are the Turkic people of Russia living in Southern Siberia on the left bank of the Khakass-Minusinsk basin.

The Khakass are divided into four ethnographic groups: Kachins (Khaash, Khaas), Sagais (Sa Ai), Kyzyls (Khyzyl) and Koibals (Khoybal). The latter were almost completely assimilated by the Kachins. Anthropologically, the Khakass are divided into two types of mixed origin, but generally belonging to a large Mongoloid race: Ural (Biryusa, Kyzyls, Beltyrs, part of the Sagais) and South Siberian (Kachins, steppe part of the Sagais, Koibals). Both anthropological types contain significant Caucasoid characteristics and occupy an intermediate position between the Caucasoid and Mongoloid races.

The Khakass language belongs to the Uyghur group of the Eastern Xiongnu branch of the Turkic languages. According to another classification, it belongs to the independent Khakass (Kyrgyz-Yenisei) group of Eastern Turkic languages. The Kumandins, Chelkans, Tubalars (belong to the Western Turkic North-Altai group), as well as the Kyrgyz, Altaians, Teleuts, Telengits (belong to the Western Turkic Kyrgyz-Kypchak group) are close to Khakass in language. The Khakass language includes four dialects: Kachin, Sagai, Kyzyl and Shor. Modern writing is based on the Cyrillic alphabet.

Story

According to ancient Chinese chronicles, the semi-legendary Xia Empire entered into a struggle with other tribes that inhabited the territory of China in the 3rd millennium BC. These tribes were called Zhun and Di (perhaps they should be considered one Zhun-di people, since they are always mentioned together). There are references that in 2600 BC. The "Yellow Emperor" launched a campaign against them. In Chinese folklore, echoes of the struggle between the “black-headed” ancestors of the Chinese and the “red-haired devils” have been preserved. The Chinese won the Thousand Year War. Some of the defeated di (Dinlins) were pushed west to Dzungaria, Eastern Kazakhstan, Altai, the Minusinsk Basin, where, mixing with the local population, they became the founders and bearers of the Afanasyevskaya culture, which, it must be said, had much in common with the culture of northern China.

The Dinlins inhabited the Sayan-Altai Highlands, the Minusinsk Basin and Tuva. Their type “is characterized by the following features: medium height, often tall, dense and strong build, elongated face, white skin color with blush on the cheeks, blond hair, nose protruding forward, straight, often aquiline, light eyes.” Anthropologically, the Dinlins constitute a special race. They had a “sharply protruding nose, a relatively low face, low eye sockets, a wide forehead - all these signs indicate that they belonged to the European trunk. The South Siberian type of Dinlins should be considered proto-European, close to Cro-Magnon. However, the Dinlins had no direct connection with the Europeans, being a branch that diverged back in the Paleolithic.

The direct heirs of the Afanasyevites were the tribes of the Tagar culture, which survived until the 3rd century. BC. The Tagarians were first mentioned in the “Historical Notes” of Sima Qian in connection with their subjugation by the Huns in 201 BC. e. At the same time, Sima Qian describes the Tagars as Caucasians: “they are generally tall, with red hair, a ruddy face and blue eyes; black hair is considered a bad sign.”

It should also be mentioned that there are gaps in the documented history of the Xiongnu from about 1760 to 820, then to 304 BC. It is only known that at this time the ancestors of the Xiongnu, defeated by the Rong and Chinese, retreated to the north of the Gobi, where their distribution area also included the Minusinsk Basin. Thus, the “visit” of the Huns to Sayan-Altai under Mode was far from the first.

In the V-VIII centuries, the Kyrgyz were subordinated to the Rourans, the Turkic Khaganate, and the Uyghur Khaganate. Under the Uighurs, there were quite a lot of Kyrgyz: more than 100 thousand families and 80 thousand soldiers. In 840, they defeated the Uyghur Khaganate and formed the Kyrgyz Khaganate, which was the hegemon in Central Asia for more than 80 years. Subsequently, the Kaganate broke up into several principalities, which maintained relative independence until 1207, when Jochi was included in the Mongol Empire, where they were located from the 13th to the 15th centuries. It is noteworthy that Chinese historiographers in more ancient times designated the Kyrgyz ethnonyms “gegun”, “gyangun”, “gegu”, and in the 9th-10th centuries (during the existence of the Kyrgyz Kaganate) they began to convey the name of the ethnic group in the form “hyagyas”, which, in general, -this corresponds to the Orkhon-Yenisei "Kyrgyz". Russian scientists, studying this issue, called the ethnonym “Khyagyas” in the pronunciation form “Khakass”, which is convenient for the Russian language.

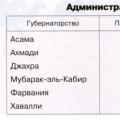

In the late Middle Ages, tribal groups of the Khakass-Minusinsk basin formed the ethnopolitical association Khongorai (Hoorai), which included four ulus principalities: Altysar, Isar, Altyr and Tuba. Since 1667, the Khoorai state was a vassal of the Dzungar Khanate, where most of its population was resettled in 1703.

The Russian development of Siberia began in the 16th century, and in 1675 the first Russian fort in Khakassia was built on Sosnovy Island (on the site of today's city of Abakan). However, Russia managed to finally gain a foothold here only in 1707. The annexation was carried out under strong pressure from Peter 1. From July 1706 to February 1707, he issued three personal decrees demanding the founding of a fort on Abakan and thereby ending the hundred-year war of annexing Khakassia. After the annexation, the territory of Khakassia was administratively divided between four counties - Tomsk, Kuznetsk, Achinsk and Krasnoyarsk, and from 1822 it became part of the Yenisei province.

With the arrival of the Russians, the Khakass were converted to the Christian faith, but for a long time they believed in the power of shamans, and certain rituals of worshiping spirits remained to this day. At the end of the 19th century, the Khakass were divided into five ethnic groups: Sagais, Kachins, Kyzyls, Koibals and Beltyrs.

Life and traditions

The traditional occupation of the Khakass was semi-nomadic cattle breeding. Horses, cattle and sheep were bred, which is why the Khakass called themselves a “three-herd people.” Hunting (a male occupation) occupied a significant place in the economy of the Khakass (except for the Kachins). By the time Khakassia joined Russia, manual farming was widespread only in the subtaiga regions. In the 18th century, the main agricultural tool was the abyl - a type of ketmen; from the late 18th - early 19th centuries, the plow - salda. The main crop was barley, from which talkan was made. In the autumn in September, the subtaiga population of Khakassia went out to collect pine nuts (khuzuk). In the spring and early summer, women and children went out to fish for edible kandyk and saran roots. Dried roots were ground in hand mills, milk porridge was made from flour, cakes were baked, etc. They were engaged in tanning leather, rolling felt, weaving, lasso weaving, etc. In the 17th-18th centuries, the Khakass of the subtaiga regions mined ore and were considered skilled smelters gland. Small smelting furnaces (khura) were built from clay.

At the head of the steppe thoughts were the Begi (Pigler), called ancestors in official documents. Their appointment was approved by the Governor-General of Eastern Siberia. The chayzans, who were at the head of the administrative clans, were subordinate to the run. The clans (seok) are patrilineal, exogamous; in the 19th century they settled dispersedly, but clan cults were preserved. Tribal exogamy began to be violated from the middle of the 19th century. The customs of levirate, sororate, and avoidance were observed.

The main type of settlements were aals - semi-nomadic associations of several households (10-15 yurts), usually related to each other. Settlements were divided into winter (khystag), spring (chastag), and autumn (kusteg). In the 19th century, the majority of Khakass households began to migrate only twice a year - from the winter road to the summer road and back.

In ancient times, “stone towns” were known - fortifications located in mountainous areas. Legends connect their construction with the era of the struggle against Mongol rule and Russian conquest.

The dwelling was a yurt (ib). Until the mid-19th century, there was a portable round frame yurt (tirmelg ib), covered with birch bark in the summer and felt in the winter. To prevent the felt from getting wet from rain and snow, it was covered with birch bark on top. Since the middle of the 19th century, stationary log yurts “agas ib”, six-, eight-, decagonal, and among the bais, twelve- and even fourteen-angled, began to be built on winter roads. At the end of the 19th century, felt and birch bark yurts no longer existed.

There was a fireplace in the center of the yurt, and a smoke hole (tunuk) was made in the roof above it. The hearth was made of stone on a clay tray. An iron tripod (ochyh) was placed here, on which there was a cauldron. The door of the yurt was oriented to the east.

The main type of clothing was a shirt for men, and a dress for women. For everyday wear they were made from cotton fabrics, while for holiday wear they were made from silk. The men's shirt was cut with polki (een) on the shoulders, with a slit on the chest and a turn-down collar fastened with one button. Folds were made at the front and back of the collar, making the shirt very wide at the hem. The wide, gathered sleeves of the polkas ended in narrow cuffs (mor-kam). Square gussets were inserted under the arms. The women's dress had the same cut, but was much longer. The back hem was made longer than the front and formed a small train. The preferred fabrics for dresses were red, blue, green, brown, burgundy and black. Polkas, gussets, cuffs, borders (kobee) running along the hem, and the corners of the turn-down collar were made of fabric of a different color and decorated with embroidery. Women's dresses were never belted (except for widows).

Belt clothing for men consisted of lower (ystan) and upper (chanmar) pants. Women's trousers (subur) were usually made of blue fabric (so that) and in their cut they did not differ from men's ones. The trouser legs were tucked into the tops of the boots, because the ends were not supposed to be visible to men, especially the father-in-law.

Men's chimche robes were usually made of cloth, while holiday robes were made of corduroy or silk. The long shawl collar, sleeve cuffs and sides were trimmed with black velvet. The robe, like any other men's outerwear, was necessarily belted with a sash (khur). A knife in a wooden sheath decorated with tin was attached to its left side, and a flint inlaid with coral was hung behind the back by a chain.

Married women always wore a sleeveless vest over their robes and fur coats on holidays. Girls and widows were not allowed to wear it. The sigedek was sewn in a swing, with a straight cut, from four glued layers of fabric, thanks to which it retained its shape well, and was covered with silk or corduroy on top. Wide armholes, collars and floors were decorated with a rainbow border (cheeks) - cords sewn closely in several rows, hand-woven from colored silk threads.

In spring and autumn, young women wore a swinging caftan (sikpen, or haptal) made of two types of thin cloth: cut and straight. The shawl collar was covered with red silk or brocade, mother-of-pearl buttons or cowrie shells were sewn onto the lapels, and the edges were bordered with pearl buttons. The ends of the cuffs of the sikpen (as well as other women's outerwear) in the Abakan Valley were made with a beveled protrusion in the shape of a horse's hoof (omah) - to cover the faces of shy girls from intrusive glances. The back of the straight sikpen was decorated with floral patterns, the armhole lines were trimmed with a decorative orbet stitch - “goat”. The cut-off sikpen was decorated with appliqués (pyraat) in the shape of a three-horned crown. Each pyraat was trimmed with a decorative seam. Above it was embroidered a pattern of “five petals” (pis azir), reminiscent of a lotus.

In winter they wore sheepskin coats (ton). Loops were made under the sleeves of women's weekend coats and dressing gowns, into which large silk scarves were tied. Wealthy women instead hung long handbags (iltik) made of corduroy, silk or brocade, embroidered with silk and beads.

A typical female accessory was the pogo breastplate. The base, cut in the shape of a crescent with rounded horns, was covered with velvet or velvet, trimmed with mother-of-pearl buttons, coral or beads in the form of circles, hearts, trefoils and other patterns. Along the lower edge there was a fringe of beaded strings (silbi rge) with small silver coins at the ends. Women prepared pogo for their daughters before their wedding. Married women wore yzyrva coral earrings. Corals were bought from the Tatars, who brought them from Central Asia.

Before marriage, girls wore many braids with braided decorations (tana poos) made of tanned leather covered with velvet. From three to nine mother-of-pearl plaques (tana) were sewn in the middle, sometimes connected with embroidered patterns. The edges were decorated with a rainbow border of cells. Married women wore two braids (tulun). Old maids wore three braids (surmes). Women who had a child out of wedlock were required to wear one braid (kichege). Men wore kichege braids, and from the end of the 18th century they began to cut their hair “in a pot”.

The main food of the Khakassians was meat dishes in winter, and dairy dishes in summer. Soups (eel) and broths (mun) with boiled meat are common. The most popular were cereal soup (Charba Ugre) and barley soup (Koche Ugre). Blood sausage (han-sol) is considered a festive dish. The main drink was ayran made from sour cow's milk. Ayran was distilled into milk vodka (airan aragazi).

Religion

Shamanism has been developed among the Khakass since ancient times. Shamans (kamas) were engaged in treatment and led public prayers - taiykh. On the territory of Khakassia, there are about 200 ancestral cult places where sacrifices (a white lamb with a black head) were made to the supreme spirit of the sky, the spirits of mountains, rivers, etc. They were designated by a stone stele, an altar or a pile of stones (obaa), next to which birch trees were installed and tied red, white and blue chalama ribbons. The Khakass revered Borus, a five-domed peak in the Western Sayan Mountains, as a national shrine. They also worshiped the hearth and family fetishes (tess).

After joining Russia, the Khakass were converted to Orthodoxy, often by force. However, despite this, ancient traditions are still strong among the Khakassians. So, since 1991, a new holiday began to be celebrated - Ada-Hoorai, based on ancient rituals and dedicated to the memory of ancestors. It is usually held at old places of worship. During prayer, after each ritual walk around the altar, everyone kneels (men on the right, women on the left) and falls face to the ground three times in the direction of sunrise.

- (obsolete name Abakan or Minusinsk Tatars) people in Khakassia (62.9 thousand people), a total of 79 thousand people in the Russian Federation (1991). Khakass language. Khakass believers are Orthodox, traditional beliefs are preserved... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

- (self-names Tadar, Khoorai) a nationality with a total number of 80 thousand people, living mainly on the territory of the Russian Federation (79 thousand people), incl. Khakassia 62 thousand people. Khakass language. Religious affiliation of believers: traditional... ... Modern encyclopedia

KHAKASSES, Khakassians, units. Khakas, Khakass, husband. The people of the Turkic linguistic group, constituting the main population of the Khakass Autonomous Region; former name Abakan Turks. Ushakov's explanatory dictionary. D.N. Ushakov. 1935 1940 ... Ushakov's Explanatory Dictionary

KHAKASSES, ov, units. as, a, husband. The people who make up the main indigenous population of Khakassia. | wives Khakassia, I. | adj. Khakassian, aya, oh. Ozhegov's explanatory dictionary. S.I. Ozhegov, N.Yu. Shvedova. 1949 1992 … Ozhegov's Explanatory Dictionary

- (self-name Khakass, outdated name Abakan or Minusinsk Tatars), people in the Russian Federation (79 thousand people), in Khakassia (62.9 thousand people). The Khakass language is a Uyghur group of Turkic languages. Orthodox believers are preserved... ...Russian history

Ov; pl. The people who make up the main population of Khakassia, partly Tuva and the Krasnoyarsk Territory; representatives of this people. ◁ Khakas, a; m. Khakaska, and; pl. genus. juice, date scam; and. Khakassian, oh, oh. X. tongue. * * * Khakass (self-name Khakass,... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

Khakassians Ethnopsychological Dictionary

KHAKASS- the people of our country, who have inhabited the taiga territories of Southern Siberia in the valley of the Middle Yenisei near the cities of Abakan, Achinsk and Minusinsk since ancient times. In Tsarist Russia, the Khakass, like a number of other Turkic peoples, were called Minusinsk, Achinsk and... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary of Psychology and Pedagogy

Khakassians- KHAKAS, ov, plural (ed Khakas, a, m). The people who make up the main indigenous population of the Republic of Khakassia within Russia, located in the southeast of Siberia, partly of Tuva and the Krasnodar Territory (the old name is the Abakan or Minusinsk Tatars);... ... Explanatory dictionary of Russian nouns

The people living in the Khakass Autonomous Okrug and partly in the Tuva Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic and the Krasnoyarsk Territory. Number of people: 67 thousand people. (1970, census). The Khakass language belongs to the Turkic languages. Before the October Revolution of 1917 they were known under the general name... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Books

- Siberia. Ethnicities and cultures. Peoples of Siberia in the 19th century. Issue 1, L. R. Pavlinskaya, V. Ya. Butanaev, E. P. Batyanova, Authors of the collective monograph "Peoples of Siberia in the 19th century." continue the research begun in 1988, devoted to the analysis of the number and settlement of the peoples of Siberia in the 19th century. Teamwork… Category:

The main small Turkic-speaking indigenous people of Khakassia are the Khakass, or as they call themselves “Tadar” or “Tadarlar”, who live mainly in. The word “Khakas” is rather artificial, adopted into official use with the establishment of Soviet power to designate the inhabitants of the Minusinsk Basin, but never took root among the local population.

The Khakass people are heterogeneous in ethnic composition and consist of different subethnic groups:

In the notes of the Russians, for the first time in 1608, the name of the inhabitants of the Minusinsk Basin was heard as Kachins, Khaas or Khaash, when the Cossacks reached the lands ruled by the local Khakass prince Tulka.

The second isolated subethnic community is the Koibali or Khoibal people. They communicate in the Kamasin language, which does not belong to the Turkic languages, but belongs to the Samoyed Uralic languages.

The third group among the Khakass are the Sagais, mentioned in the chronicles of Rashid ad-Din about the conquests of the Mongols. In historical documents, the Sagais appeared in 1620 that they refused to pay tribute and often beat tributaries. Among the Sagais, a distinction is made between the Beltyrs and the Biryusins.

The next separate group of Khakass are considered to be the Kyzyls or Khyzyls on Black Iyus in.

Telengits, Chulyms, Shors and Teleuts are close to the Khakass culture, language and traditions.

Historical features of the formation of the Khakass people

The territory of the Minusinsk Basin was inhabited by inhabitants even before our era, and the ancient inhabitants of this land reached a fairly high cultural level. What remains from them are numerous archaeological monuments, burial grounds and burial mounds, petroglyphs and steles, and highly artistic gold items.

Excavations of ancient mounds made it possible to discover priceless artifacts of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic, Iron Age, Afanasyevskaya culture (III-II millennium BC), Andronovo culture (mid-II millennium BC), Karasuk culture (XIII-VIII centuries BC.). No less interesting are the finds of the Tatar culture (VII-II centuries BC) and the very original Tashtyk culture (I century BC -V century AD).

Chinese chronicles named the population of the upper Yenisei in the middle of the 1st millennium BC. Dinlins and described them as fair-haired and blue-eyed people. In the new era, the Khakass lands and pastures began to be developed by Turkic-speaking peoples, who formed the distinctive early feudal monarchy of the ancient Khakass (Yenisei Kyrgyz) in the 6th century, and in the 6th-8th centuries. First and Second Turkic Khaganates. At this time, a civilization of nomads with its material culture and spiritual values arose here.

The state of the Khakass (Yenisei Kyrgyz), although it was multi-ethnic in composition, turned out to be stronger than the huge Khaganates of the Turgesh, Turks, and Uyghurs and became a large steppe empire. It developed a strong social and economic foundation and experienced rich cultural development.

The state created by the Yenisei Kyrgyz (Khakas) lasted for more than 800 years and collapsed only in 1293 under the blows of the ancient Mongols. In this ancient state, in addition to cattle breeding, the inhabitants were engaged in agriculture, sowing wheat and barley, oats and millet, and using a complex system of irrigation canals.

In the mountainous regions there were mines where copper, silver and gold were mined; the skeletons of iron smelting furnaces still remain; jewelers and blacksmiths were skilled here. In the Middle Ages, large cities were built on the land of the Khakass. G.N. Potanin mentioned about the Khakass that they had settled large settlements, a calendar and a lot of gold things. He also noted a large group of priests who, being free from taxes to their princes, knew how to heal, tell fortunes, and read the stars.

However, under the onslaught of the Mongols, the chain of development of the state was interrupted, and the unique Yenisei runic letter was lost. The Minusinsk and Sayan peoples were tragically thrown back far back in the historical process and fragmented. In yasak documents, the Russians called this people Yenisei Kyrgyz, who lived in separate uluses along the upper reaches of the Yenisei.

Although the Khakass belong to the Mongoloid race, they have traces of obvious influence on their anthropological type from Europeans. Many historians and researchers of Siberia describe them as white-faced with black eyes and a round head. In the 17th century, their society had a clear hierarchical structure, each ulus was headed by a prince, but there was also a supreme prince over all uluses, power was inherited. They were subordinated to ordinary hardworking cattle breeders.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz lived on their own land until the 18th century, then they fell under the rule of the Dzungar khans and were resettled several times. The Kyrgyz Kyshtyms became the closest of the ancestors of the Khakass. They were engaged in cattle breeding, the Kyzyls hunted a lot in the taiga, collected pine nuts and other gifts from the taiga.

Russian explorers began exploring the native lands of the Khakass in the 16th century and continued in the 17th century. From Mangazeya they actively moved south. The princes of the Yenisei Kyrgyz greeted the newcomers unfriendlyly and organized raids on the Cossack forts. At the same time, raids by the Dzungars and Mongols on the land of the ancient Khakass began to become more frequent from the south.

The Khakass had no choice but to turn to the Russian governors with a timely request for help in defending against the Dzungars. The Khakass became part of Russia when in 1707 Peter I ordered the construction of the Abakan fort. After this event, peace came to the lands of the “Minusinsk region”. The Abakan fort entered a single defensive line together with the Sayan fort.

With the settlement of the Minusinsk Basin by Russians, they mastered the right bank of the Yenisei, favorable for agriculture, and the Khakass lived mainly on the left bank. Ethnic and cultural ties arose, and mixed marriages appeared. The Khakass sold fish, meat, and furs to the Russians, and went to their villages to help harvest the crops. The Khakass received the opportunity and gradually overcame fragmentation and rallied into a single people.

Khakass culture

Since ancient times, Chinese and Confucian, Indian and Tibetan, Turkic, and later Russian and European values have dissolved in the original culture of the Khakass. The Khakass have long considered themselves people born of the spirits of nature and adhered to shamanism. With the arrival of Orthodox missionaries, many were baptized into Christianity, secretly conducting shamanic rituals.

The sacred peak for all Khakassians is the five-domed Borus, a snow-capped peak in the western Sayan Mountains. Many legends tell about the prophetic elder Borus, identifying him with the biblical Noah. The greatest influence on the culture of the Khakass was shamanism and Orthodox Christianity. Both of these components have entered the mentality of the people.

The Khakass highly value camaraderie and collectivism, which helped them survive among the harsh nature. The most important feature of their character is mutual assistance and mutual assistance. They are characterized by hospitality, hard work, cordiality and pity for the elderly. Many sayings talk about giving what someone in need needs.

The guest is always greeted by a male owner; it is customary to inquire about the health of the owner, family members, and their livestock. Conversations about business are always conducted respectfully, and special greetings should be made to elders. After the greetings, the owner invites the guests to taste kumis or tea, and the hosts and guests begin the meal over an abstract conversation.

Like other Asian peoples, the Khakass have a cult of their ancestors and simply elders. Old people have always been the keepers of priceless worldly wisdom in any community. Many Khakass sayings talk about respect for elders.

Khakassians treat children with gentleness, special restraint and respect. In the traditions of the people, it is not customary to punish or humiliate a child. At the same time, every child, as always among nomads, must know their ancestors today up to the seventh generation or, as before, up to the twelfth generation.

The traditions of shamanism prescribe to treat the spirits of the surrounding nature with care and respect; numerous “taboos” are associated with this. According to these unwritten rules, Khakass families live among virgin nature, honoring the spirits of their native mountains, lakes and river reservoirs, sacred peaks, springs and forests.

Like all nomads, the Khakass lived in portable birch bark or felt yurts. Only by the 19th century did yurts begin to be replaced by stationary log one-room and five-walled huts or log yurts.

In the middle of the yurt there was a fireplace with a tripod where food was prepared. The furniture was represented by beds, various shelves, forged chests and cabinets. The walls of the yurt were usually decorated with bright felt carpets with embroidery and appliqué.

Traditionally, the yurt was divided into male and female halves. On the man's half were stored saddles, bridles, lassos, weapons, and gunpowder. The woman's half contained dishes, simple utensils, and things of the housewife and children. The Khakass made dishes and necessary utensils, many household items themselves from scrap materials. Later, dishes made of porcelain, glass and metal appeared.

In 1939, linguists created a unique writing system for the Khakassians based on the Russian Cyrillic alphabet; as a result of establishing economic ties, many Khakassians became Russian-speaking. There was an opportunity to get acquainted with the richest folklore, legends, sayings, fairy tales, and heroic epics.

The historical milestones of the formation of the Khakass people, their formed worldview, the struggle of good against evil, the exploits of heroes are set out in the interesting heroic epics “Alyptyg Nymakh”, “Altyn-Aryg”, “Khan Kichigei”, “Albynzhi”. The guardians and performers of heroic epics were the highly revered “haiji” in society.

In 1604-1703, the Kyrgyz state, located on the Yenisei, was divided into 4 possessions (Isar, Altyr, Altysar and Tuba), in which the ethnic groups of modern Khakass were formed: Kachins, Sagais, Kyzyls and Koibals.

Before the revolution, the Khakass were called “Tatars” (Minusinsk, Abakan, Kachin). At the same time, in documents of the 17th - 18th centuries, Khakassia was called “Kyrgyz land” or “Khongorai”. The Khakassians use “khoorai” or “khyrgys-khoorai” as a self-name.

In the 17th - 18th centuries, the Khakass lived in scattered groups and were dependent on the feudal elite of the Yenisei Kyrgyz and Altyn Khans. In the first half of the 18th century they were included in the Russian state. The territory of their residence was divided into “zemlits” and volosts, headed by bashlyks or princes.

The term “Khakas” appeared only in 1917. In July, a union of foreigners from the Minusinsk and Achinsk districts was formed under the name “Khakas”, which was derived from the word “Khyagas”, mentioned in ancient times in Chinese chronicles.

On October 20, 1930, the Khakass Autonomous Region was formed in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, and in 1991 the Republic of Khakassia was formed, which became part of Russia.

The traditional occupation of the Khakass is semi-nomadic cattle breeding. They raised cattle, sheep and horses, which is why they were sometimes called the “three-herd people.” In some places, pigs and poultry were raised.

Not the least place in the Khakassian economy was occupied by hunting, which was considered an exclusively male occupation. But farming was widespread only in some areas where barley was the main crop.

In former times, women and children were engaged in gathering (edible kandyk and saran roots, nuts). The roots were ground in hand mills. To collect cedar cones, they used a nokh, which was a large chock mounted on a thick pole. This pole was pressed into the ground, and striking the tree trunk.

The main type of Khakass villages were aals - associations of 10-15 farms (usually related). Settlements were divided into winter (khystag), spring (chastag), summer (chaylag), and autumn (kusteg). Khystag was usually located on the river bank, and chaylag in cool places near groves.

The dwelling of the Khakassians was a yurt (ib). Until the middle of the 19th century, there was a portable round frame yurt, which was covered with birch bark in the summer and with felt in the winter. In the century before last, stationary log polygonal yurts spread. In the center of the dwelling there was a fireplace made of stone, above which a smoke hole was made in the roof. The entrance was located on the east side.

The traditional male clothing of the Khakass was a shirt, and the traditional female clothing was a dress. The shirt had polyki (een) on the shoulders, a slit on the chest and a turn-down collar, which was fastened with one button. The hem and sleeves of the shirt were wide. The dress did not differ too much from the shirt, except perhaps in length. The back hem was longer than the front.

The lower part of men's clothing consisted of lower (ystan) and upper (chanmar) pants. Women also wore trousers (subur), which were usually made of blue fabric and were practically no different in appearance from men. Women always tucked the ends of their pants into the tops of their boots, since men were not supposed to see them. Men and women also wore robes. Married women wore a sleeveless vest (sigedek) over their robes and fur coats on holidays.

The decoration of Khakass women was a pogo bib, which was trimmed with mother-of-pearl buttons and patterns made with coral or beads. A fringe was made along the lower edge with small silver coins at the ends. The traditional food of the Khakassians was meat and dairy dishes. The most common dishes were meat soups (eel) and broths (mun). The festive dish is blood sausage (han-sol). The traditional drink is ayran, made from sour cow's milk.

The main holidays of the Khakass were associated with cattle breeding. In the spring, the Khakass celebrated Uren Khurty - the holiday of killing the grain worm, the traditions of which were designed to protect the future harvest. At the beginning of summer, Tun Payram was celebrated - the holiday of the first ayran - at this time the first milk appeared. The holidays were usually accompanied by sports competitions, which included horse racing, archery, wrestling, etc.

The most revered genre of Khakass folklore is the heroic epic (alyptyg nymakh), performed to the accompaniment of musical instruments. The heroes of the songs are heroes (alyps), deities, and spirits. Storytellers were respected in Khakassia and in some places were even exempt from taxes.

In the old days, the Khakass developed shamanism. Shamans (kamas) also served as healers. On the territory of Khakassia, many places of worship have been preserved where sacrifices (usually rams) were made to the spirits of the sky, mountains, and rivers. The national shrine of the Khakass is Borus, a peak in the Western Sayan Mountains.

In the first millennium AD. The Kyrgyz dominated in Southern Siberia. In the 9th century they created their own state on the middle Yenisei - the Kyrgyz Kaganate. The Chinese called them “Khyagasy” - a term that later, in the Russian version, took the form “Khakasy”.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Kirghiz Kaganate fell under the blows of the Tatar-Mongols. But a century and a half later, when the Mongol Empire, in turn, collapsed, the tribes of the Minusinsk Basin created a new political entity - Khongorai, led by the Kyrgyz nobility. The Khongorai tribal community served as the cradle of the Khakass people.

The Kirghiz stood out for their belligerence and fierce temperament. Among many peoples of Southern Siberia, mothers frightened their children: “The Kirghiz will come, catch you and eat you.”

Therefore, the Russians, who appeared here in the 17th century, met fierce resistance. As a result of bloody wars, the territory of Khongorai was practically depopulated and in 1727, according to the Treaty of Burin with China, it was transferred to Russia. In pre-revolutionary Russian documents it is known as “Kyrgyz land” as part of the Yenisei province.

The revolution of 1917 became the cause of a new act of tragedy for the Khakass. The rules imposed by the Soviet government aroused sharp rejection by the people, who considered a person with 20 horses to be poor. Khakass partisan detachments continued to fight in the mountainous regions, according to official data, until 1923. By the way, it was in the struggle against them that the famous Soviet writer Arkady Gaidar spent his youth. And collectivization caused a new outbreak of armed resistance, which was brutally suppressed.

And yet, from the point of view of ethno-political history, being part of Russia as a whole played a positive role for the Khakassians. In the 19th-20th centuries, the process of formation of the Khakass people was completed. Since the 1920s, the ethnonym “Khakass” has been approved in official documents.

Before the revolution, foreign departments and councils existed on the territory of the Minusinsk district. In 1923, the Khakass national district was formed, which was subsequently transformed into an autonomous region of the Krasnoyarsk Territory, and since 1991 - into a republic, an independent subject of the Russian Federation.

The number of the Khakass people also grew steadily. Today Russia is inhabited by about 80 thousand Khakass (an increase in number of more than 1.5 times over the twentieth century).

For centuries, Christianity and Islam waged an attack on the traditional religion of the Khakass - shamanism. Officially, on paper, they have achieved great success, but in real life, shamans still enjoy much more respect among the Khakass than priests and mullahs.

White Wolf - Chief shaman

Khakassians.

Khakass shaman Egor Kyzlasov in full robes (1930)).

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the Khakass made collective prayers to heaven, from whom they usually asked for a good harvest and lush grass for livestock. The ceremony took place on a mountain peak. Up to 15 lambs were sacrificed to heaven. They were all white, but always with a black head.

When someone in the family was sick for a long time, one should turn to the birch tree for help. Praying to the birch tree was an echo of that distant time when people considered trees to be their ancestors. The patient’s relatives chose a young birch tree in the taiga, tied colored ribbons to its branches, and from that moment on it was considered a shrine, the guardian spirit of this family.

For many centuries, the main occupation of the Khakass was cattle breeding. According to ancient legends, the “master of the cattle” was a powerful spirit - Izykh Khan. In order to appease him, Izykh Khan was given a horse as a gift. After a special prayer with the participation of a shaman, the chosen horse was woven into its mane with a colored ribbon and released into the wild. Now they called her exclusively “izyh”. Only the head of the family had the right to ride it. Every year in spring and autumn he washed his mane and tail with milk and changed his ribbons. Each Khakass clan chose horses of a certain color as their horses.

In spring and autumn, flamingos sometimes fly over Khakassia, and the man who caught this bird could woo any girl.

They put a red silk shirt on the bird, tied a red silk scarf around its neck and went with it to their beloved girl. The parents had to accept the flamingo and give their daughter in return. In this case, kalym was not required.

Bride and matchmaker

Since 1991, a new holiday began to be celebrated in Khakassia - Ada-Hoorai, dedicated to the memory of our ancestors. During prayer, after each ritual walk around the altar, everyone kneels (men on the right, women on the left) and falls face to the ground three times, facing the sunrise.

Khakas people Traditional activities of Khakass

Khakas people Traditional activities of Khakass School encyclopedia What country is Kuwait located in?

School encyclopedia What country is Kuwait located in? Why is Palmyra, a city in Syria, under special protection by UNESCO?

Why is Palmyra, a city in Syria, under special protection by UNESCO?